The Complete Guide to Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is one of two types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). UC, as its name implies, means ‘ulcers’ from inflammation of the colon or large intestine. UC can extend from the rectum up to the small intestine and can cause destruction of other organs.

Overview of ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is one of two types of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). The other IBD is Crohn’s disease which can affect any part of the small and large intestine. Ulcerative colitis refers to ‘ulcers’ from inflammation of the colon or large intestine. UC can extend from the rectum up to the small intestine and can cause destruction of other organs.1

Immune disturbances are thought to be the underlying destructive mechanism whereby immunoglobulins or antibodies are produced that target the lining and cells of the colon.2

The disease is persistent with periods of remission. Over time, the destructive antibodies erode the absorptive surface (villi) of the large intestine, destroy mucus-secreting structures, and form craters or ulcers that ultimately develop granulation tissue or scar tissue that festers and grows. Scar tissue builds up and leads to pseudopolyps (fake protrusions).

How common is UC?

UC is three times more common than Crohn’s disease and affects one million people in the United States.34

Women and Caucasians are more likely affected. 20-25% of cases occur in people under the age of 20 and there is a peak in diagnosis in two time periods from the ages 15-25 and 55-65. However, any age of onset is possible.5

What is pancolitis?

The full name for pancolitis is Pan-ulcerative colitis and means that the UC affects the entire large intestine from rectum, to descending (sigmoid) colon, the transverse colon, the left colon, and extending to the right colon all the way to the ileum or the last section of the small intestine. It is believed to be affect 20% of UC patients.

Signs and symptoms of UC

Rectal bleeding, diarrhea, mucus drainage from the rectum, a sense of fullness, lower abdominal pain, and dehydration are the hallmarks of the disease. Fevers, bloat or distention, weight loss, and signs of infection are other possible symptoms.

UC can cause eye disturbances, lung problems, skin nodules, spinal instability and arthritis. The liver and bile systems can become damaged. About 6% of people with UC have symptoms of inflammation in other organs, with the eye being most common.6

Up to 39% of people with UC have arthritis of various joints, with back pain a common feature, as the spine is often affected. The sacroiliac joint is affected in 40% as seen by X-ray.7

UC is categorized as mild if there are less than four bowel movements (BMs) a day along with rectal bleeding, moderate if there is bowel bleeding and more than four BMs a day, and severe if there are more than four bowel movements and evidence of widespread disease with low protein levels in the blood.

What causes UC?

The exact cause of ulcerative colitis has not been conclusively demonstrated, but it is believed to be linked to genetics, environment, and immune disturbances. Diet may play a secondary role along with an exaggerated immune response to bacterial exposure.89

Lack of antioxidants, stress, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, oral contraceptives, and milk intake are also risk factors for UC development.10 UC commonly runs in families. And multiple genes are thought to be linked to UC, one of them (CDH1), can increase the risk of colon cancer.1112

An appendectomy performed prior to the age of 20 for appendicitis had a protective affect against UC.1314

Immune disturbances

Specific antibodies, ANCA (a white blood cell antibody) and ASCA (an antibody to one species of yeast, not Candida) are well-known associated features of IBD.1516171819

Likewise, self-generated antibodies to the cells of the lining of the colon are thought to be important factors in UC development.

Environmental factors

Environmental factors, such as a large number of sulfate-reducing bacteria that make sulfides, are seen with ulcerative colitis compared to people who make less sulfides. Likewise, the bacterial microbiome or microflora is altered in patients with active UC disease.20 One species of bacteria known as Klebsiella is less abundant in the small intestine of people with UC, which is corrected after the diseased large intestine is removed.

NSAID use

NSAID (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) use in UC exacerbates symptoms and are not recommended for these patients.21

Other causal factors

Other factors that may be associated with ulcerative colitis include the following:

- Lower levels of Vitamins A and E, both antioxidants, are found in 16% of children with UC.22

- Stress factors may aggravate symptoms or cause flares of UC.23

- Smoking may have a protective effect in UC.24

How is UC Diagnosed?

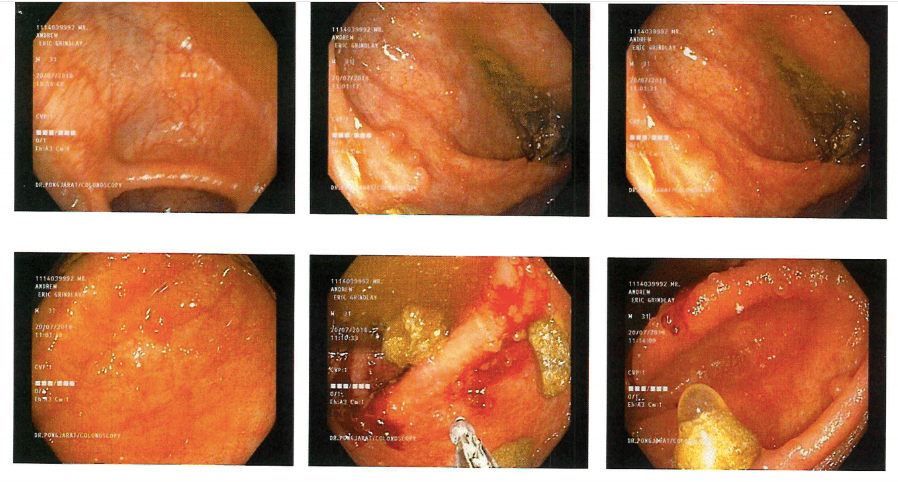

A biopsy is needed to make the diagnosis, and this can be done via colonoscopy. Blood work can help determine nutritional status. X-ray or CT is helpful in differentiating UC from Crohn’s disease, since Crohn’s can also affect the small intestine.

Fistulas found only in Crohn’s can help determine the exact cause of the rectal bleeding and symptoms. Biopsies will show a reddened lining with possible ulcers that begin in the rectum and extend through the large bowel continuously without any areas that are unaffected.

Negative stool cultures to detect infections and the absence of another diagnosis for 6 months is crucial for confirming the diagnosis along with a biopsy consistent with inflammation.

The severity of the disease is divided into proctosigmoiditis, which is limited to the rectum and possibly the sigmoid colon, left-sided disease that extends up the left side of the sigmoid colon and stops at the point where the sigmoid turns right at the spleen, and extensive disease that goes beyond the spleen to involve the rest of the large intestine.

Radiologic tests may include the following:

- Plain X-ray

- Barium enema with contrast

- Ultrasonography – can detect how deep the UC extends into the bowel wall25

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – measures depth of penetration, thickening, ulcers, and fistulas26

- Computed tomography (CT) scan-monitoring disease, abscess detection

- Radionuclide studies

- Angiography-dye infused into the arteries/veins of the intestines

MRI and ultrasound are preferred due to lack of radiation exposure compared with CT and X-rays.

How does it affect the colon?

The bowel wall is usually swollen, the muscle becomes enlarged, and fat accumulates. The disease is mostly limited to the superficial lining called the mucosa with some penetration into the deeper layer. Abscesses form after the tissue is destroyed, resulting in erosion into blood vessels that leads to bruising, hemorrhages, and rectal bleeding.

Laboratory studies

Lab tests are useful for diagnosing and tracking the progression of UC. Here are the types of laboratory studies used:

- Antibody tests: ANCA, pANCA, and ASCA

- Positive pANCA and Negative ASCA suggest UC

- Negative pANCA and Positive ASCA suggest Crohn’s27

- 60-80% of UC people have a positive ANCA

- ANCA and ASCA not predictive of disease severity

- Complete blood cell (CBC) count

- Metabolic panel

- Inflammation markers ESR and C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Stool studies

How is UC treated?

Treatments typically focus on reducing inflammation and then managing the symptoms. Much of this begins with diet.

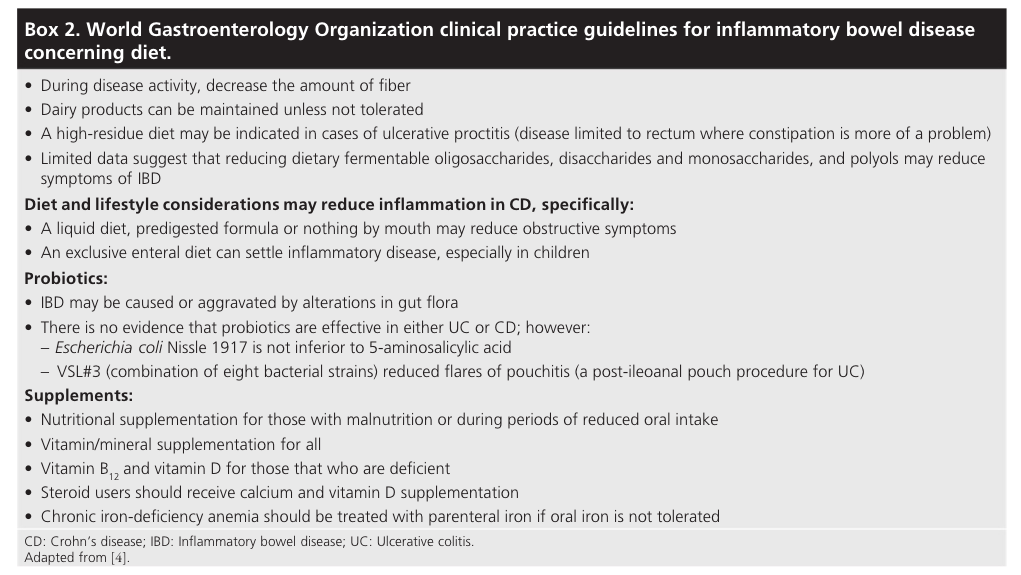

Ulcerative colitis diet

Changing your diet is the first-line approach to managing UC.

Individualized dietary changes are encouraged, though dietary adjustments are less helpful in UC compared to irritable bowel syndrome. Avoiding stimulants such as coffee and sugar alcohols such as sorbitol and xylitol are suggested. Raw fruits and vegetables are best avoided.

Medications

Medications are the mainstay of treatment in mild to moderate cases of UC.

- Mild cases start with topical budesonide foam or mesalazine suppositories

- Left-sided disease includes mesalazine suppository and oral mesalazine

- Oral steroids can be used until there is a response to mesalazine

- Long-term therapy is needed to prevent relapses

Budesonide

A a potent steroid that has minimal systemic effects compared to traditional steroids. It also is a potent anti-inflammatory medication with less risk of complications or side effects.28 The long-term risks of steroids such as prednisone include osteoporosis, poor wound healing, weight gain, mood disturbances, and inability to fight off infections.

Stronger medications

More potent drugs such as tacrolimus, infliximab, adalimumab, cyclosporine, and golimumab may be needed in hard to manage cases.29

Cyclosporine

Effective for severe, active ulcerative colitis and is as effective as infliximab.30

Tacrolimus is another effective agent to control active UC, but long-term safety has not been demonstrated.31 Cyclosporine and tacrolimus cannot be used long-term due to kidney toxicity, and infliximab requires another agent to limit the acquisition of human anti-mouse antibody (HAMA).

The HAMA reaction is an allergic reaction to mouse antibodies (monoclonal antibodies or Mab) such as a rash or more severe such as kidney failure. It can also reduce the effectiveness of future treatment with mouse antibodies (Mabs). Mice were used to produce antibodies that attacked the human immune response found in autoimmune diseases and cancers.

Infliximab

Infliximab reduces the risk of complete colon removal compared to no treatment, and there were fewer complications and readmission to the hospital.

Adalimumab

The drug adalimumab (trade name, Humira) is approved for use in UC that is unresponsive to immunosuppressants such as steroids. Clinical responses were obtained as early as eight weeks and continued for 52 weeks in a long-term maintenance study.3233

Golimumab

Golimumab is approved for treatment of UC and for maintenance after a clinical trial demonstrated that a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving subcutaneous injections responded well by week 6.34

Tofacitinib

FDA-approved tofacitinib, a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor helps treat and maintain remission in people with moderate to severe UC and is the first oral medication available for long-term use. It appears that 10mg was slightly more effective than 5mg of tofacitinib.3536

Surgery

Surgery, along with medications, may be needed for severe cases. Hospitalization and intravenous steroids are commonly used initially. Urgent surgery is required for ‘toxic megacolon,’ a massive dilation of the colon or uncontrolled rectal bleeding.

Surgery is reserved for instances where abnormal cells or cancer are found, long-term steroid dependence, or long duration of the disease (7-10 years).

The types of surgeries include total removal of the large intestine with ileostomy, where surgeons attach the end of the small intestine, the ileum, to an opening on the outside of the abdomen with a pouch, and the removal of the large bowel, which necessitates the reattchment of the ileum to the rectum or anus.373839

Probiotics for ulcerative colitis

There are several mechanisms by which probiotics work to correct or reduce the inflammatory destruction in UC which is thought to be related to aggressive bacterial activity in the colon.

These ‘good’ bacteria protect the lining of the intestines preventing the ‘bad’ bacteria access to the underlying tissue. Probiotics encourage mucus production that protects against invasive bacteria adherence to the lining of the colon.

A third mechanism is that probiotics stimulate the immune system to release protective antibodies such as IgA and other defensive chemicals. By activating the immune system, there is more anti-inflammatory substances and less pro-inflammatory substances, and this is one of the most important mechanisms by which probiotics help UC.40

Best probiotics for UC

The two most effective probiotics are E.coli Nissle and VSL#3 in the treatment of UC based on the clinical trial evidence. E. coli Nissle (Mutaflor) is a non-pathogenic bacteria and was found to be just as effective as mesalamine in a large number of clinical trials.

Another more recent trial reported that VSL#3 probiotic which consists of eight species of bacteria was effective against UC. Those species are:

- Bifidobacterium breve

- B. longum

- B. infantis

- Lactobacillus acidophilus

- L. plantarum

- L. paracasei

- L. bulgaricus

- Streptococcus thermophilus

For more comprehensive coverage, see our article on supplements and probiotics.

Alternative therapies for ulcerative colitis

Some herbal remedies to consider:

- Devil’s claw

- Cinnamon

- Peppermint oil for cramping

- Slippery elm

- Mexican yam

- Curcumin

- Wheatgrass juice

- Fenugreek

Stress and ulcerative colitis

Any chronic disease is aggravated by stress – not to mention being a major cause of it. Thus, UC can potentially be helped with the practice of:

- Yoga

- Meditation

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

- Biofeedback

- Hypnotherapy

- Massage

- Acupuncture

- Guided Imagery

- [Guideline] Matsuoka K, Kobayashi T, Ueno F, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2018 Mar. 53 (3):305-53. [Medline]. [Full Text].

- Himmel ME, Hardenberg G, Piccirillo CA, Steiner TS, Levings MK. The role of T-regulatory cells and Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of human inflammatory bowel disease. Immunology. 2008 Oct. 125(2):145-53. [Medline].

- Garland CF, Lilienfeld AM, Mendeloff AI, Markowitz JA, Terrell KB, Garland FC. Incidence rates of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in fifteen areas of the United States. Gastroenterology. 1981 Dec. 81(6):1115-24. [Medline].

- Cotran RS, Collins T, Robbins SL, Kumar V. Pathologic Basis of Disease. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders; 1998.

- Jang ES, Lee DH, Kim J, Yang HJ, Lee SH, Park YS. Age as a clinical predictor of relapse after induction therapy in ulcerative colitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009 Sep-Oct. 56(94-95):1304-9. [Medline]

- Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Yu N. The prevalence of extraintestinal diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Apr. 96(4):1116-22. [Medline].

- de Vlam K, Mielants H, Cuvelier C, De Keyser F, Veys EM, De Vos M. Spondyloarthropathy is underestimated in inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and HLA association. J Rheumatol. 2000 Dec. 27(12):2860-5. [Medline].

- Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007 Jul 26. 448(7152):427-34. [Medline].

- Lindberg E, Magnusson KE, Tysk C, Jarnerot G. Antibody (IgG, IgA, and IgM) to baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), yeast mannan, gliadin, ovalbumin and betalactoglobulin in monozygotic twins with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1992 Jul. 33(7):909-13. [Medline]. [Full Text].

- See Matsuoka.

- See Matsuoka.

- Barrett JC, Lee JC, Lees CW, et al. Genome-wide association study of ulcerative colitis identifies three new susceptibility loci, including the HNF4A region. Nat Genet. 2009 Dec. 41(12):1330-4. [Medline]. [Full Text].

- Andersson RE, Olaison G, Tysk C, Ekbom A. Appendectomy and protection against ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2001 Mar 15. 344(11):808-14.[Medline].

- Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, et al. Stress and exacerbation in ulcerative colitis: a prospective study of patients enrolled in remission. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 May. 95(5):1213-20. [Medline].

- Peeters M, Joossens S, Vermeire S, Vlietinck R, Bossuyt X, Rutgeerts P. Diagnostic value of anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae and antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Mar. 96(3):730-4. [Medline].

- Dubinsky MC, Ofman JJ, Urman M, Targan SR, Seidman EG. Clinical utility of serodiagnostic testing in suspected pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Mar. 96(3):758-65. [Medline].

- Hoffenberg EJ, Fidanza S, Sauaia A. Serologic testing for inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr. 1999 Apr. 134(4):447-52. [Medline].

- Kaditis AG, Perrault J, Sandborn WJ, Landers CJ, Zinsmeister AR, Targan SR. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody subtypes in children and adolescents after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998 Apr. 26(4):386-92. [Medline].

- Duggan AE, Usmani I, Neal KR, Logan RF. Appendicectomy, childhood hygiene, Helicobacter pylori status, and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a case control study. Gut. 1998 Oct. 43(4):494-8. [Medline]. [Full Text].

- Almeida MG, Kiss DR, Zilberstein B, Quintanilha AG, Teixeira MG, Habr-Gama A. Intestinal mucosa-associated microflora in ulcerative colitis patients before and after restorative proctocolectomy with an ileoanal pouch. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008 Jul. 51(7):1113-9. [Medline].

- Felder JB, Korelitz BI, Rajapakse R, Schwarz S, Horatagis AP, Gleim G. Effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Aug. 95(8):1949-54. [Medline].

- Bousvaros A, Zurakowski D, Duggan C, et al. Vitamins A and E serum levels in children and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease: effect of disease activity. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998 Feb. 26(2):129-35. [Medline].

- See Levenstein.

- See Matsuoka.

- See Matsuoka.

- McNamara D. New IBD guidelines aim to simplify care. Medscape Medical News. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/892853. February 20, 2018; Accessed: June 6, 2018.

- See Bernstein.

- Barber J Jr. FDA approves Uceris for ulcerative colitis. Medscape Medical News. Jan 18, 2013. Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/777917. Accessed: January 28, 2013.

- Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, et al. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr. 106(4):644-59, quiz 660. [Medline].

- See Matsuoka.

- See Matsuoka.

- Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Hommes DW, et al. Adalimumab for induction of clinical remission in moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results of a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2011 Jun. 60(6):780-7. [Medline].

- Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012 Feb. 142(2):257-65.e1-3. [Medline].

- Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano CW, et al. A phase 2/3 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of subcutaneous golimumab induction therapy in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC): Pursuit SC [abstract #943d]. Presented at: Digestive Disease Week; San Diego, California; May 21, 2012.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new treatment for moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis [news release]. Available at https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm609225.htm. May 30, 2018; Accessed: May 31, 2018.

- Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, et al, for the OCTAVE Induction 1, OCTAVE Induction 2, et al. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017 May 4. 376 (18):1723-36. [Medline]. [Full Text].

- Esteve M, Gisbert JP. Severe ulcerative colitis: at what point should we define resistance to steroids?. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 Sep 28. 14(36):5504-7. [Medline]. [Full Text].

- Shen B. Crohn’s disease of the ileal pouch: reality, diagnosis, and management. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009 Feb. 15(2):284-94. [Medline].

- Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P. Treatment of severe steroid refractory ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 Sep 28. 14(36):5508-11. [Medline]. [Full Text].

- Fedorak RN, “Probiotics in the management of ulcerative colitis” Gastroenterology & hepatology vol. 6,11 (2010): 688-90.

Comments