The Best Probiotics for IBD and IBS: Everything You Need to Know!

Are probiotics effective for ulcerative colitis and Crohn's? We'll talk about about the role of bacteria in gut health, gut dysbiosis, the role of probiotics, and the best probiotics for IBS and IBD.

Your gut is home to trillions of bacteria, both good and bad. There are more bacteria in your gut than the total number of cells in your body. A good balance of these bacteria is one of the factors that gives you a healthy life.

What happens when the bad bacteria take over? Is there any link between bacterial imbalance, IBD, and IBS? What is the role of probiotics in restoring this imbalance? These are the questions patients ask me.

This article will talk in detail about the role of bacteria in gut health, gut dysbiosis, the role of probiotics, and the best probiotics for IBS and IBD.

Let’s get to it.

Our current understanding of gut microbiota

The gut contains more than 1,000 species of bacteria that live in a close relationship with each other and their surrounding gut cells. These bacteria thrive on nutrients derived from sugars and amino acids present in our food. The microenvironment they create in the gut is called the gut microbiota or the gut microbiome.

In return, these bacteria perform several important functions for the human host, which include:

Nutrient metabolism

The microbiota thrives on the food we eat and in the process, they help metabolize a lot of nutrients.

For instance, members of the genus Bacteroides help in the fermentation and metabolism of sugars, amino acids, and lipids.12

Antimicrobial protection

Perhaps the most important function of the gut microbiota is to keep a check on the growth of bad bacteria. Probiotics achieve this by strengthening the gut mucosal barrier by increasing the production of thick mucin and by closing the gaps between the intestinal cells (enhanced mucosal integrity). This prevents the bad bacteria from attaching to the gut cells and crossing them to gain entry into the bloodstream.34

Other mechanisms include increased production of antimicrobial substances like immunoglobulins.5

Immune modulation

The human gut contains an immune system of its own called the gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT). The gut microbiota helps in the development of GALT. In addition, it acts as an interface between GALT and other immune controlling cells like T and B lymphocytes.67

Controlling inflammation

As mentioned, the commensal microbiota acts an interface between the outside world and the gut’s intrinsic immune system. The commensals transfer the signals from the bacteria or harmful substances in the gut lumen to the T and B cells of the gut. This leads to T and B cell differentiation and production of inflammatory mediators like cytokines, interleukins, and tumor growth factors.8 These mediators cause gut inflammation leading to increased gut permeability and microbial imbalance.

Gut-brain axis

The gut contains a complicated neurological system, sometimes referred to as the “second brain.” There exists a bidirectional channel of communication between the gut and the brain. The microbiota can change the way your brain functions by altering the concentration of gut-derived neurohormones like cholecystokinin and bombesin. For instance, an increase in cholecystokinin is implicated in panic and pain disorders and bombesin overproduction leads to stress and anxiety910. It also alters the immune system and inflammatory chemicals that can affect the brain function.11

There are just a few of the several crucial functions of microbiota in the human body.

Gut dysbiosis and its relation to IBD and IBS

The balance of the intestinal microbiota is beneficial for human health. An imbalance in the ratio between good and bacteria gives rise to a condition called gut dysbiosis that can significantly alter your health.

Dysbiosis can be due to three main reasons:1213

- Unchecked growth of the harmful bacteria.

- Excessive loss of good bacteria.

- A lack in the diversity of the gut microbiota.

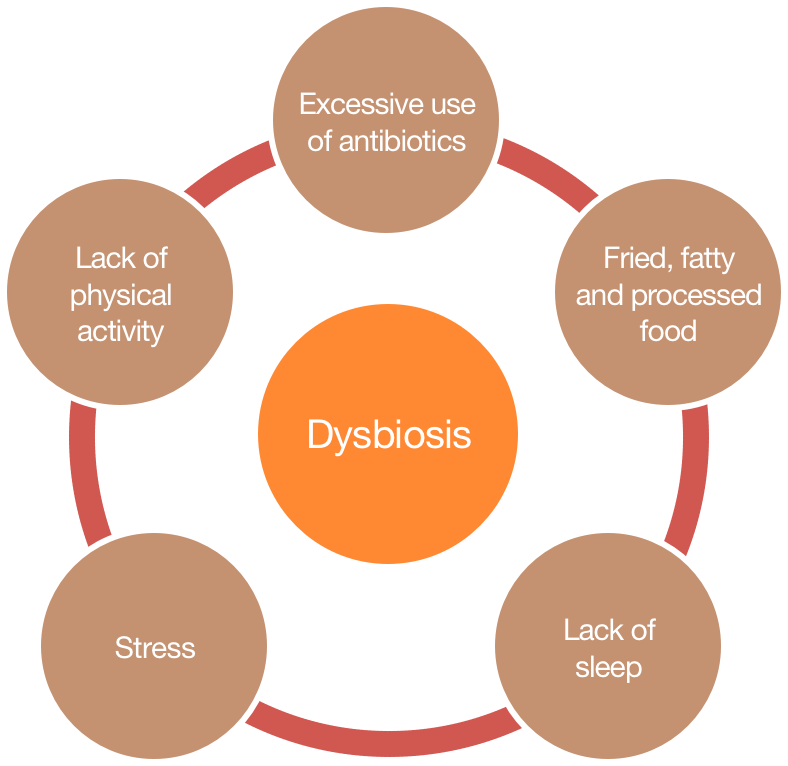

There are several risk factors that can make you prone to dysbiosis. Some of these factors are as follows:1415

The research suggests that dysbiosis plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of IBD and IBS.

The three reasons that lead to dysbiosis could exist simultaneously in IBD and IBS. The growth of probiotics belonging to the phylum Firmicutes is globally reduced in IBD and IBS. The population of pathogenic subgroups, like the phylum Proteobacteria, is higher among IBD and IBS sufferers. Finally, in IBD and IBS, the gut loses the microbial diversity as well.1617

What are probiotics?

The term probiotic is derived from a Greek word meaning ‘for life.’ The definition of probiotics has changed over time.

Initially, it was believed that probiotics are useful substances produced by the bacteria that have favorable effects on the health. Currently, probiotics are defined as “live microbial feed supplements which beneficially affect the host animal by improving microbial balance.”18

Not all bacteria are probiotics. For bacteria to be classified as probiotics, they need to fulfill the following criteria:19 20, 21

- They should be able to tolerate the harsh acidic environment of the stomach and alkaline environment of the intestines.

- They need to be able to attach themselves properly to the gut epithelial cells.

- They should have antimicrobial activity against the pathogenic bacteria.

- They should be able to degrade the bile salts in the gut.

Only bacteria having these properties are classified as probiotics. Otherwise, they will either be destroyed by the harsh environment of the gut and will never reach the desired site or they will not be able to adhere to the gut wall.

Here are some of the common probiotics with their locations in the human body:

| Genus | Location in Human Body | Food Sources | Common Probiotic Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus2930 | Vagina, gastrointestinal tract, oral cavity | Yogurt, wine, cheese, sourdough, sauerkraut, pickles, and other fermented products | L. acidophilus, L. fermentum, L. casei, L. plantarum, L. paracasei, L. johnsonii, L. rhamnosus, L. brevis, L. salivarius, L. delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus, L. sakei, and L. bulgaricus |

| Bifidobacterium28 | Vagina, gastrointestinal tract, oral cavity | Yogurt, wine, cheese, sourdough, sauerkraut, pickles, and other fermented products | Bifidobacterium infantis, B. breve, B. adolescentis, B. longum, B. animalis subsp animalis, B. bifidum, B. animalis subsp lactis |

| Saccharomyces27 | Gastrointestinal tract | Wine, kombucha, kefir, and other fermented foods | S. cerevisiae, S. bayanus, S. boulardii |

| Lactococcus26 | Gastrointestinal tract | Fermented foods | Lactococcus lactis subsp. Lactis |

| Enterococcus25 | Mouth, skin, intestine | Fermented foods | E. faecium, E. durans |

| Clostridium24 | Skin, gastrointestinal tract | Butter, ghee | C. butyricum |

| Escherichia23 | Skin, vagina, oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract | Meat, poultry, high-fat dairy products, meat products | E. coli Nissle 191 |

| Eubacterium22 | Gastrointestinal tract | Fermented foods | Eubacterium faecium |

What are the benefits of probiotics?

The proven health benefits of these species and the quality of evidence available is summarized as follows:

| Probiotic Genus/Strain | Double-Blinded Trials Available | Health Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus383940 | Yes | Lactobacillus species improve iron levels, have antidiabetic properties, protect against cardiovascular diseases, improve the probiotic microbiota in the gut, ameliorate ulcers and infections, have anti-inflammatory properties, prevent traveler and antibiotic-related diarrhea, boost immunity, have anti-obesity effects, combat cancer and urogenital infections, and alleviate pain and allergy. |

| Bifidobacterium353637 | Yes | Bifidobacteria stimulate the immune system, offer protection against cancers and cardiovascular disease, help treat diarrhea, reduce inflammatory bowel disease symptoms, and help with infections and reduce allergy symptoms. |

| Escherichia34 | Yes | E. coli Nissle 191 has been implicated in the management of diabetes, metastatic melanoma, multiple sclerosis, anemia, pituitary disorders, diarrhea short stature, muscle wasting, hemophilia, gout, IBS, and IBD. |

| Eubacterium33 | Yes | Has a possible role as an anti-inflammatory agent, has antineoplastic properties32, regulates blood sugar, boosts the immune system, and might regulate body weight. |

| Enterococcus | No | Might help clean-up antibiotic resistant variant of bacteria. |

| Saccharomyces31 | Yes | Upholds intestinal mucosal integrity, boosts immune function, inhibits inflammation, helpful with diarrheal diseases, helps increase uptake of nutrients like zinc, might offer protection against cardiovascular and Alzheimer’s disease. |

Probiotics for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s

There is an overwhelming amount of research showing that probiotics have a crucial role in the management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD).

These are the three fundamental factors that come into play:

- Anti-inflammatory and immune modulating roles: Research suggests that probiotics have tremendous anti-inflammatory and immune modulating benefits. You can read more about the effects of exaggerated inflammation and immune response and their link to IBD on the Supplements for IBS and IBD page.

- Modulating gut barrier function: The disruption of the mucosal gut barrier is believed to be the key pathology in IBD. The use of probiotics stabilizes this barrier. Probiotics achieve this by inhibiting the early deaths of the gut cells (apoptosis), by increasing the production of thick mucus, and by tightening the junctions between the gut cells.2223

- Altering the probiotic/pathogen balance: As mentioned before, the use of probiotics can alter the probiotic/pathogen balance in favor of probiotic bacteria.

Research has suggested that different strains of probiotics are useful in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s. So in this section, both of these conditions will be discussed separately.

Probiotics for ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a form of IBD in which extensive areas of the gut are involved and it mainly affects the colon (large gut).

The most researched probiotic when it comes to ulcerative colitis is VSL#3, a high potency combination probiotic supplement. It contains four strains of lactobacilli (L. delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus, Lactobacillus casei, L. plantarum, and L. acidophilus) and three strains of bifidobacteria (B. infantis, B. longum, and B. breve).

In the first Randomized Controlled Trial, 144 patients were randomized to receive either VSL#3 or a placebo for eight weeks. The participants took two sachets of VSL#3 twice a day with meals (a total of 3,600 billion CFU/day.24).

Both groups were already receiving the standard 5-aminosalicylic acid (ASA) and/or immunosuppressant therapy at a stable dose.

The score used to assess the effects of the probiotic was the Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity Index (UCDAI). This index uses variables like stool frequency, rectal bleeding, appearance of the gut mucosa, and the physician’s appearance rating of disease activity.

Results were encouraging and the participants using VSL#3 experienced a significant reduction in the disease activity as shown by their lower UCDAI scores. Also, the VSL#3 group had a greater chance of disease remission and a lower chance of disease recurrence after the completion of trial.25

In another double-blinded, randomized control trial, the efficacy of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in inducing remission in UC was compared to the standard mesalazine therapy. The study included 327 participants who were randomized into two groups to either receive the probiotic preparation or the standard mesalazine therapy.

The probiotic group was given a probiotic preparation once a day that contained 2.5–25×109 viable bacteria in an enteric coated pill (a coating that helps the bacteria survive the perilous trip down the gut). The standard therapy group was given 500mg mesalazine three times a day. The study continued for twelve months and the response to the treatments was measured using clinical assessment and endoscopic and histological appearances of the gut.

At the end of the twelve-month study period, only 36% of the probiotic group showed a relapse. This was in comparison to 34% to the mesalazine group that had a relapse. In other words, the probiotic preparation containing E. coli Nissle 1917 was equally as effective as the standard mesalazine therapy in preventing UC relapse. In addition, the probiotic group had much better tolerability and fewer side effects compared to the mesalazine group.26.

In other words, you can often get the same therapeutic benefits with the use of probiotics while avoiding the side effects of medication like mesalazine.

Probiotics for Crohn’s disease

Crohn’s disease is another form of IBD in which only parts of the gut are involved and it can equally affect the small and the large gut.

The RCTs studying the relationship between probiotics and Crohn’s have produced variable results. This is partly because Crohn’s is a complex disease and can potentially involve multiple anatomical locations in the gut.

The first RCT was an Italian study where the efficacy of probiotics versus mesalazine treatment was assessed in patients with Crohn’s. The study included 32 patients who were randomly assigned into two groups, either receiving 1g of mesalazine twice daily or 1g of mesalazine plus a probiotic preparation containing Saccharomyces boulardii, 1g daily, for six months. The Crohn’s Disease Activity Index was used as a tool to assess the response to the treatments.

At the end of six months, the results were encouraging. Researchers found that the probiotic group’s relapse rate was far lower (6%) compared to that of the mesalazine-only group (38%).27

Meta-analysis and multi-regression models have also shown that probiotic combination containing Saccharomyces boulardii, Lactobacillus, and VSL#3 probiotics might be beneficial for patients with Crohn’s. However, the available data is scarce.28

Probiotics for inflammatory bowel syndrome

Our understanding of Inflammatory Bowel Syndrome is evolving, but we do know that IBS shares a lot of pathological similarities with IBD. Like IBD, IBS involves mucosal inflammation, exaggerated immune response, and probiotic imbalance. You can learn more about IBS in our article, An overview of Inflammatory Bowel Syndrome (IBS).

As you’ll find in the article above, the main types are IBS with diarrhea and IBS with constipation as its predominant features. While there is tons of evidence that probiotics improve IBS symptoms in general – irrespective to the type – here we’ll only focus on research studying diarrhea or constipation-predominant IBS.

Probiotics for IBS with diarrhea

In one single-blinded RCT, researchers used a cocktail of B. lactis CUL34, B. bifidum CUL20, and Streptococcus thermophiles in a dose of 1 × 108 CFU for four weeks and compared it with a placebo. At the end of four weeks, the probiotic group showed a significant reduction in intestinal permeability scores and an improvement in the clinical symptoms of bloating, flatulence, and abdominal pain, whereas the placebo group did not show much difference from the baseline.29

In another double-blinded randomized control trial, researchers used Lactobacillus plantarum 299v in a dose of 1 × 1010 CFU for 4 weeks and compared its efficacy to a placebo. Results showed the probiotic group had a significant reduction in the frequency of their bowel movements and a reduction in abdominal pain.30

Finally, in a double-blinded randomized control trial, researchers used a mixture of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Streptococcus thermophiles, Lactobacillus plantarum, Bifidobacterium longum, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium lactis, and Bifidobacterium breve in a dose of 1 × 1010 CFU for eight weeks and compared its effects to placebo. Results showed that the probiotic group had a significant improvement in the quality of life and stool consistency compared to the placebo.31

Probiotics for IBS with constipation

A British study used Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173 010 based preparations in a dose of 2.5 × 1010 for four weeks and compared it to a placebo. Results showed that the probiotic group achieved greater symptomatic relief, had a better gut transient time that led to resolution of constipation, and improvement in abdominal distention as well.32

French research using Bifidobacterium animalis DN-173 010 produced similar results. This study lasted for six weeks. Results showed that the probiotic group had a remarkable improvement in their quality of life, bowel frequency, abdominal discomfort, and bloating.33

Recommendations

As discussed in this article, there is a moderate amount of evidence to support the use of probiotic supplements for conditions like ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s, and inflammatory bowel syndrome. However, the successful use of probiotics depends on a number of variables.

The Correct Strains of Probiotics

Not all probiotics are the same. Only certain species have been shown to work for different health conditions. For instance, in ulcerative colitis, Lactobacillus sp have shown no clinical value in improving symptoms. The only types of probiotics that have been demonstrated to have benefits were VSL#3 and E. coli Nissle.

Here is a summary of probiotics best suited for UC, Crohn’s, and IBS respectively:

| Condition | Best Suited Probiotics Based on Research |

|---|---|

| Ulcerative Colitis |

|

| Crohn’s |

|

| IBS with Diarrhea | A cocktail of Streptococcus thermophiles, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacterium |

| IBS with Constipation | Predominantly Bifidobacterium but Lactobacilli have also shown benefits |

Probiotics in the right concentration and amount

Another thing you must keep in mind is that the probiotic bacteria have to survive the harsh environments of the stomach and the gut to arrive in the desired place. For enough bacteria to reach the desired place, you have to take the right amount of probiotic bacteria. As a general rule of the thumb, the higher the CFU value, the better the results.

You should use a probiotic supplement containing no less than several billion CFU of probiotic bacteria.

Another factor to consider is the mode of transporting the bacteria to their desired site. Try to use preparations in which bacteria are encapsulated in stomach or enteric-resistant coatings. This aids the bacteria in reaching the target gut sites unharmed.

Duration of use of probiotics

This is perhaps the most important reason why most people fail to see any results with probiotics.

Your gut is an extremely complicated ecosystem. The damage done to the microbiota through years of unhealthy dietary and lifestyle choices can’t be undone or reversed overnight. You need to have some patience.

In most of the randomized controlled trials, the participants had to use probiotic supplementations for several weeks to months to see any beneficial outcomes.

You’ll likely have to take the probiotic supplements for several months before you can expect to see favorable outcomes.

Healthy lifestyle

Finally, if you wish to have good gut health in the long run, then you have to combine the use of probiotics with a healthy and active lifestyle. This will give your gut the chance to heal naturally and supports the probiotic supplements for maximum effect.

A couple of things you can try:

Eat a healthy diet

Keep yourself hydrated. Keep the use of processed, fatty, and fried food to a minimum. You can learn more about specific dietary recommendations for IBD and IBS in another of our amazing articles.

Avoid overuse of antibiotics

The effects of antibiotics on the gut microbiome can be enormous and long-lasting. According to research, even a single dose of antibiotics can sometimes cause irreversible damage to your gut microbiota.

More interestingly, in animal models, researchers have found that the use of antibiotics totally eliminated certain probiotic strains from the animals and they were never able to recover from the damage. What’s more astounding is that some of the animals even passed the probiotic deficiencies to their offspring.34

Keep active and de-stress

A higher level of cortisol is associated with a greater incidence of gut dysbiosis.

Introduce more probiotics into your diet naturally

You can make use of fermented foods like kombucha, kefir, yogurt, and so on.

- Cantarel BL, Lombard V, Henrissat B. Complex carbohydrate utilization by the healthy human microbiome. PLoS One. 2012;7:e28742

- Hooper LV, Wong MH, Thelin A, Hansson L, Falk PG, Gordon JI. Molecular analysis of commensal host-microbial relationships in the intestine. Science. 2001;291:881–884

- Salzman NH, Underwood MA, Bevins CL. Paneth cells, defensins, and the commensal microbiota: a hypothesis on intimate interplay at the intestinal mucosa. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:70–83

- Podolsky DK, Lynch-Devaney K, Stow JL, Oates P, Murgue B, DeBeaumont M, Sands BE, Mahida YR. Identification of human intestinal trefoil factor. Goblet cell-specific expression of a peptide targeted for apical secretion. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6694–6702

- He B, Xu W, Santini PA, Polydorides AD, Chiu A, Estrella J, Shan M, Chadburn A, Villanacci V, Plebani A, et al. Intestinal bacteria trigger T cell-independent immunoglobulin A(2) class switching by inducing epithelial-cell secretion of the cytokine APRIL. Immunity. 2007;26:812–826

- Chung H, Pamp SJ, Hill JA, Surana NK, Edelman SM, Troy EB, Reading NC, Villablanca EJ, Wang S, Mora JR, et al. Gut immune maturation depends on colonization with a host-specific microbiota. Cell. 2012;149:1578–1593

- Hasegawa M, Osaka T, Tawaratsumida K, Yamazaki T, Tada H, Chen GY, Tsuneda S, Núñez G, Inohara N. Transitions in oral and intestinal microflora composition and innate immune receptor-dependent stimulation during mouse development. Infect Immun. 2010;78:639–65

- Yasmine Belkaid, et al. Role of the Microbiota in Immunity and inflammation. Cell. 2014 Mar 27; 157(1): 121–141

- Bueno L, et al. Effects of inflammatory mediators on gut sensitivity. Can J Gastroenterol. 1999 Mar;13 Suppl A:42A-46A

- Moody TW, et al. Bombesin-like peptides and associated receptors within the brain: distribution and behavioral implications. Peptides. 2004 Mar;25(3):511-20

- Eamonn M.M. Quigley. The Gut-Brain Axis and the Microbiome: Clues to Pathophysiology and Opportunities for Novel Management Strategies in Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). J Clin Med. 2018 Jan; 7(1): 6

- Arianna K. DeGruttola, et al. Current understanding of dysbiosis in disease in human and animal models. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 May; 22(5): 1137–1150

- Simon Carding, et al. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015; 26: 10.3402/mehd.v26.26191

- M. P. Francino. Antibiotics and the Human Gut Microbiome: Dysbioses and Accumulation of Resistances. Front Microbiol. 2015; 6: 1543

- Serena Schippa, et al. Dysbiotic Events in Gut Microbiota: Impact on Human Health. Nutrients. 2014 Dec; 6(12): 5786–5805

- Josephine Ni, et al. Gut microbiota and IBD: causation or correlation? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Oct; 14(10): 573–584

- Eleonora Distrutti, et al. Gut microbiota role in irritable bowel syndrome: New therapeutic strategies. World J Gastroenterol. 2016 Feb 21; 22(7): 2219–2241

- Fuller R. Probiotics in man and animals. Journal of Applied Bacteriology. 1989;66(5):365–378

- Mercenier A, Lenoir-Wijnkoop I, Sanders ME. Physiological and functional properties of probiotics. International Dairy Federation. 2008;429:2–6

- Joint FAO/WHO Working Group Report on Drafting Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food. Ontario, Canada: 2002. http://www.fao.org/es/ESN/Probio/probio.htm

- Saarela M, Mogensen G, Fondén R, Mättö J, Mattila-Sandholm T. Probiotic bacteria: safety, functional and technological properties. Journal of Biotechnology. 2000;84(3):197–215

- Yan F, Polk DB. Probiotic bacterium prevents cytokine-induced apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 2002;277:50959–65

- Ahrne S, Hagslatt ML. Effect of lactobacilli on paracellular permeability in the gut. Nutrients 2011;3:104–17

- 900 billion CFU/sachet

- Antonio Tursi, et al. Treatment of Relapsing Mild-to-Moderate Ulcerative Colitis With the Probiotic VSL#3 as Adjunctive to a Standard Pharmaceutical Treatment: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. The American Journal of Gastroenterology volume 105, pages 2218–2227 (2010)

- Rembacken BJ, et al. Non-pathogenic Escherichia coli versus mesalazine for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999 Aug 21;354(9179):635-9

- Guslandi M, et al. Saccharomyces boulardii in maintenance treatment of Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2000 Jul;45(7):1462-4

- Mahboube Ganji‐Arjenaki, et al. Probiotics are a good choice in remission of inflammatory bowel diseases: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:2091–2103

- J. ZENG, et al. Clinical trial: effect of active lactic acid bacteria on mucosal barrier function in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. 2008. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 28, 994–1002

- Ducrotté P, et al. Clinical trial: Lactobacillus plantarum 299v (DSM 9843) improves symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Aug 14;18(30):4012-8

- Ki Cha B, et al. The effect of a multispecies probiotic mixture on the symptoms and fecal microbiota in diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012 Mar;46(3):220-7

- Agrawal A, et al. Clinical trial: the effects of a fermented milk product containing Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173 010 on abdominal distension and gastrointestinal transit in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009 Jan;29(1):104-14

- Guyonnet D, et al. Effect of a fermented milk containing Bifidobacterium animalis DN-173 010 on the health-related quality of life and symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome in adults in primary care: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Aug 1;26(3):475-86

- M. P. Francino. Antibiotics and the Human Gut Microbiome: Dysbioses and Accumulation of Resistances. Front Microbiol. 2015; 6: 1543

Comments